A few weeks ago, I turned 28 the way I typically do: On a cold January morning, with some acknowledgement of my birth by acquaintances and cousins three times removed on Facebook, and the recipient of a few Emoji-laden, non-sensical text messages from my endearing mother. This was the age I had been waiting for – the age that my family fortuneteller predicted would be the beginning of the “good life.” And, let me tell you, the accuracy of my fortuneteller is indisputable despite his offices being housed in mildly dilapidated strip mall, wedged between “Precis Hair Salon” and “St. Elmo’s Lounge N Club.” He had predicted milestones throughout my early 20s, so I excitedly anticipated the day I turned 28.

The first day of my 28th year was rather uneventful, which was to be expected. A lesson I’ve learned in getting older is that my personal growth has never been the product of radical, overnight change. I’ve made plenty of failed midnight promises to change my life (usually while nursing a hangover and the shame of having consumed half a bag of stale semi-sweet chocolate chips). Instead, I’ve realized that I evolve incrementally, with no conscious awareness of my growth until some unexpected moment. Two years ago, I found myself cooking with two-buck chuck instead of drinking it. A year ago, I was able to help my father financially – finally (and slowly) paying him back for all the years he worked to help me.

The second and third days of my 28th year passed with little fanfare. And then, on the fourth day of my 28th year, I had somehow ended up with my long-term lesbian partner at a fine dining restaurant in San Francisco.

Venturing beyond 2-dollar sign Yelp-land is a very significant development for me. As a child, my idea of eating out was inhaling a Sourdough Jack and a box of chili cheese curly fries amid the aroma of lard and Windex at the nearest Jack-in-the-Box. This was a delicacy I could only indulge in only if I received straight-As on my report card, which reinforced my identity as the local chubby Vietnamese nerd. My other formative experiences with dining out are the number of Vietnamese restaurants my parents frequented. Like most authentic, cheap Vietnamese restaurants, you pay for the bowl of incredible pho, but not for the overworked, disinterested waiter, or the feeling of eating quickly because the number of Vietnamese people awaiting a table has exponentially increased, or the cacophony of crying babies, crashing dishes, and endless Celine Dion songs. In sum, I’m used to eating a bunch of shit, being treated like shit, and paying shit while listening to the third rotation of “The Power of Love” – and I’m perfectly fine with that.

So, here I am in this new, wonderful world of waiters who actually treat you like you have feelings. It’s fucking weird. They talk to you about the menu and ask you about your preferred flavor profile despite your only knowing two flavors – things that taste good and things that taste bad. They explain to you that sturgeon is a fish and not the occupation you had failed to become thereby destroying your mother’s dreams. They fold your cloth (!!) napkins while your lesbian partner goes to the bathroom despite the logic that she will just unfurl the napkin again. They ask you how you’re enjoying your meal.

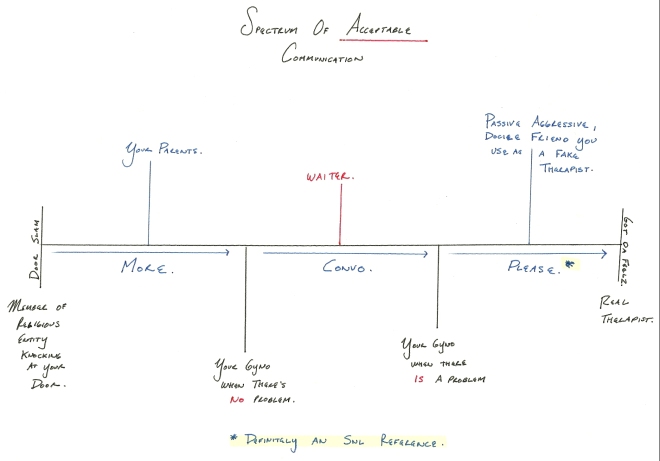

The waiter-patron conversation piece is perhaps the most interesting and difficult part of a fine dining experience. You have to talk to the waiter just enough because they’re serving you food. They determine just how much water you get, how many pats of butter you get to smear all over those sad unbuttered rolls, and how awkward the two or so hours of waiter-patron chit-chat will be. But, you don’t want have excessive conversation while your mouth is full of sturgeon (??). In order to help me assess the appropriate amount of conversation needed in a fine dining experience, I have drawn the following spectrum of acceptable communication chart, which I hope you will find helpful:

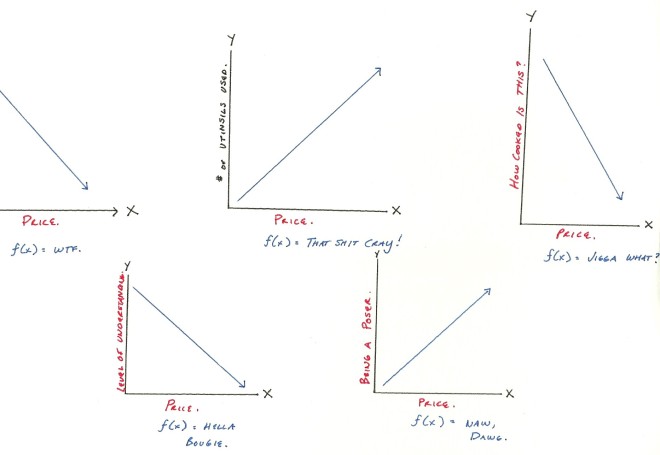

Another interesting anomaly about fine dining is the number counterintuitive relationships between food prices and factors such as size. In a normal situation, a logical assumption would be that the more you pay, the bigger your food portions will be. In a peculiar situation, such as fine dining, there are a number of irregular, illogical, inverse relationships:

- As menu prices increase, the food portions become smaller.

- As menu prices increase, the food appears to become rawer or at least not cooked on a flame.

- Although the food is less cooked and smaller in portion, the number of utensils that are available to use increase.

- As menu prices increase, the food becomes less like the thing in itself and more conceptual and esoteric (i.e. not getting an actual duck, but rather a “duck mousse”).

- The more conceptual the food becomes, the less I understand what the hell is going on or what I am eating.

To emphasize how illogical I think all of this is, I’ve taken the liberty to draw five superfluous graphs that basically just reiterate the biased generalizations I just made:

After all was done – the regulated chit-chat, the consumption of the best (and perhaps only) not-duck, and the suppression of eating like the carnivorous Neanderthal that I am – my partner received the bill. She was recovering from a terrible fever, endured a bout of overwhelming fatigue, listened to and participated in my endless observations about fine dining, and had picked up the inordinately expensive tab. I had once thought the “good life” awaiting me was to be able to afford lavish meals and to finally be a part of a fine dining-like world, shedding away my working-class perceptions about life and leisure. Yet, that sudden, magical realization of growth and the “good life” did not occur the moment we walked into that restaurant. It happened as we walked out. How wonderful, I thought, to have turned 28 with the person I love – and more wonderful to be fine with the way I experienced life in the past and fine that it informs the way I see life now. Perhaps it was leaving the restaurant, or not needing to play a part anymore, or just being bemused by the experience, but as we left all was calm, all was fine, all was “good.”