In less than 48 hours, a crew of movers will place most of my belongings in a Bay Area storage facility. My partner and I will then pack our Nissan Versa and attempt to drive it to my hometown for six months. Thereafter, we’ll figure it out. It’s the first leg of my sole New Year’s resolution for 2021 – to live as flexibly as possible, going wherever life nudges me. Although I believe all roads will lead us back to the Bay Area in the fall, the possibility of being anywhere in the latter part of 2021 is both exciting and terrifying.

This piece is not about the many irritations of moving, which are made more confounding by a global pandemic and the digital hostage interrogation that is cancelling your Comcast service. This piece is about change, risk, fear, decision making and the inertia that comes with age. Most of all, this newsletter is a tale of multiple moves over a period of 10 years – same girl, similar destinations, drastically different dispositions.

—

As some may know, I am no stranger to moving. The last decade of my life has been a shuffle of boxes and suitcases and the shedding of the extraneous physical bullshit that comes with living a single place for a few years – the random bobbleheads), the stuffed animals I forced my partner to win at claw machines, the…I don’t even know how to describe this:

My moves have a regular 2-year cadence and revolve around 3 hubs: Houston (my hometown), the San Francisco Bay Area (my adopted home), and Washington, DC (where I went to school). Despite getting older and being more familiar with the world, each subsequent relocation has felt harder and more fraught. I jumped at the opportunity to move more than a thousand miles to DC for college and another several thousand miles to San Francisco immediately after graduation. The last move I made was a 13-mile shift from San Francisco to Oakland, two cities that are separated by a single bridge with each respective skyline visible to one another on a clear day. Despite how blatantly advantageous I knew the change would be, I spreadsheet-ed and cost-benefit analyzed the fuck out of that move.

This temporary, upcoming move to Houston is within my definition of a “well duh” decision. My work is remote. My organization is supportive. My partner is excited to come with me. We have very little locking us in one place. We have the means to travel and the ability to be closer to my family. Yet, what transpired was not “well duh” decision making. It was a month of weighing pros with cons (both real and fictious). By the end of our process, I didn’t recognize the girl I had become – so steeped in fear, so anchored in the known.

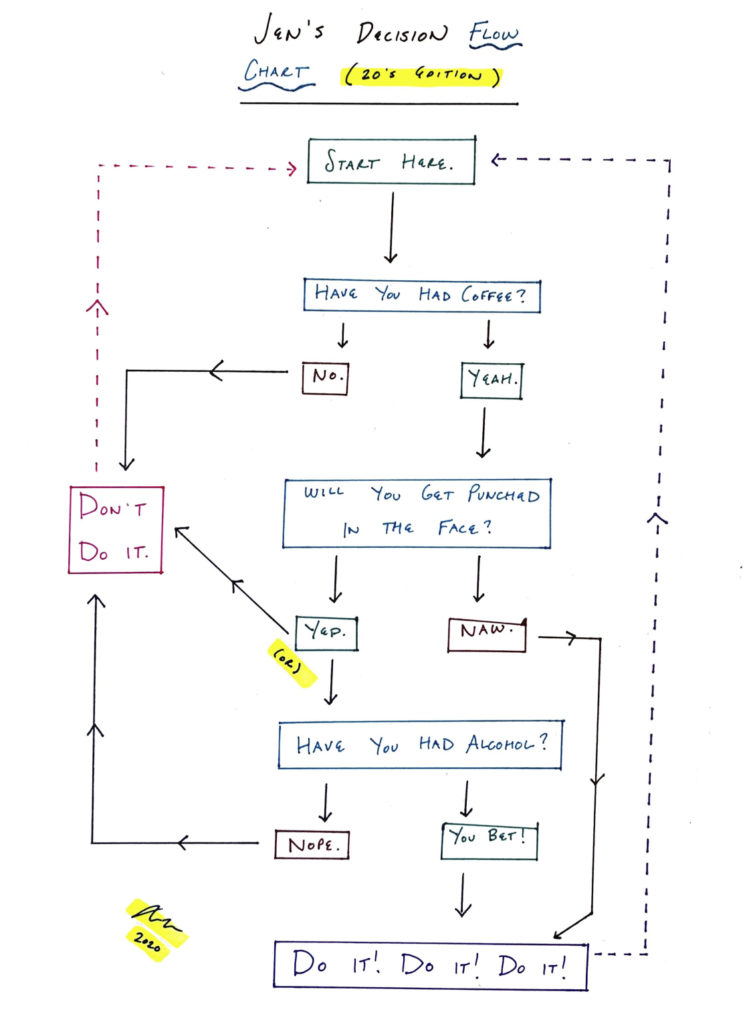

Along the journey, I developed a proclivity towards risk aversion and a decision making calculus that is more convoluted and conservative. If I could describe my decision making process in my 20s, it would look a little something like this:

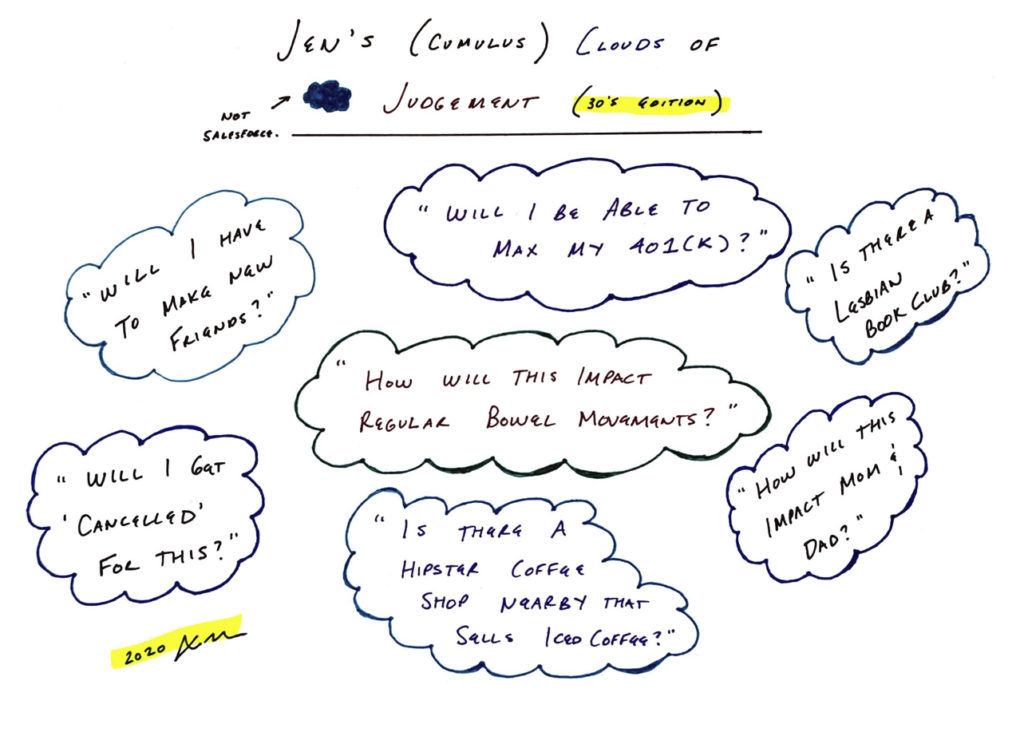

Now, in my 30s, I no longer have a very clear decision tree. Instead, the “process” has morphed into a cloudy amalgamation of considerations that can block my ability to move forward:

I’m unsure how I became so fearful and so conservative with my lifestyle. I am hoping to explore the edges of that fear in 2021. My big takeaway of 2020 is that the certain and known aren’t really as certain or as known as I had thought to be. I am hoping a year of living a little more flexibly and freely will beat back the fear just a little bit.

I wish you, your family, your chosen family, and your community and safe 2021. Here’s to a new year of living with less fear and more youthful wonder and possibility. Always stay hydrated amid decision making via coffee and alcohol, folks.