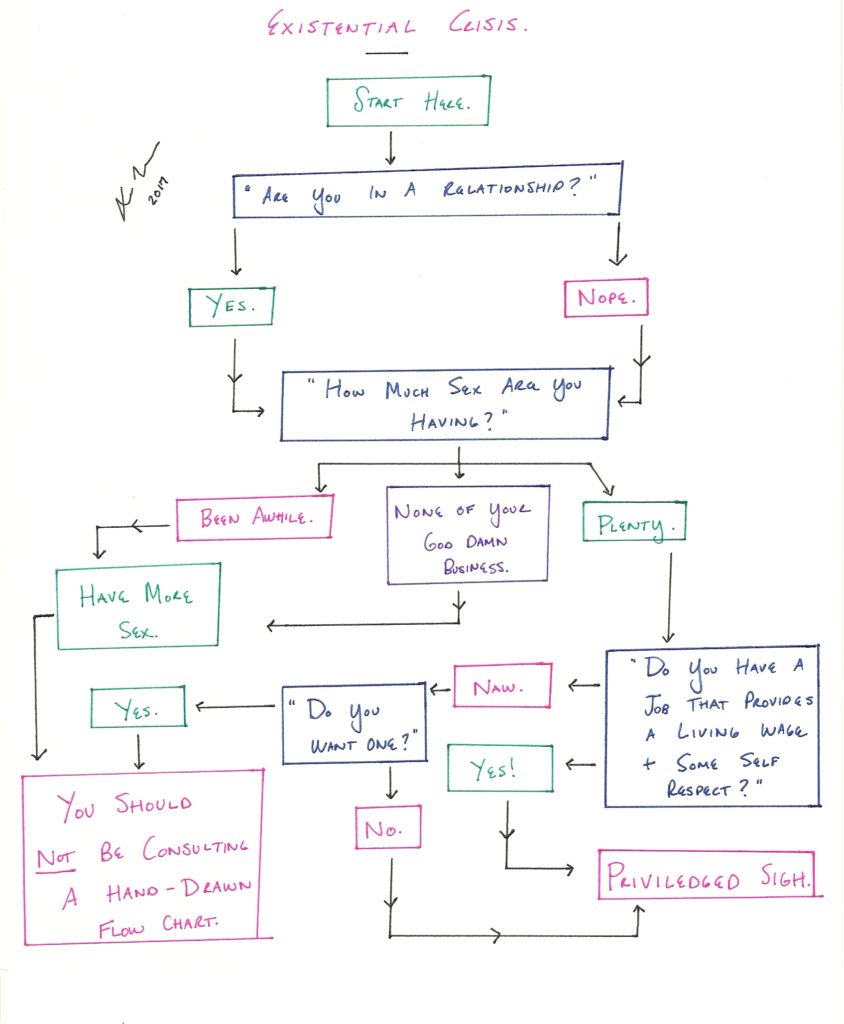

An “easy to follow” flow chart below to help you navigate your next existential crisis:

—

—

Please note that there are only two ways out of your existential crisis: “Privileged Sigh” or “Not…Consulting a Hand-Drawn Flow Chart.”

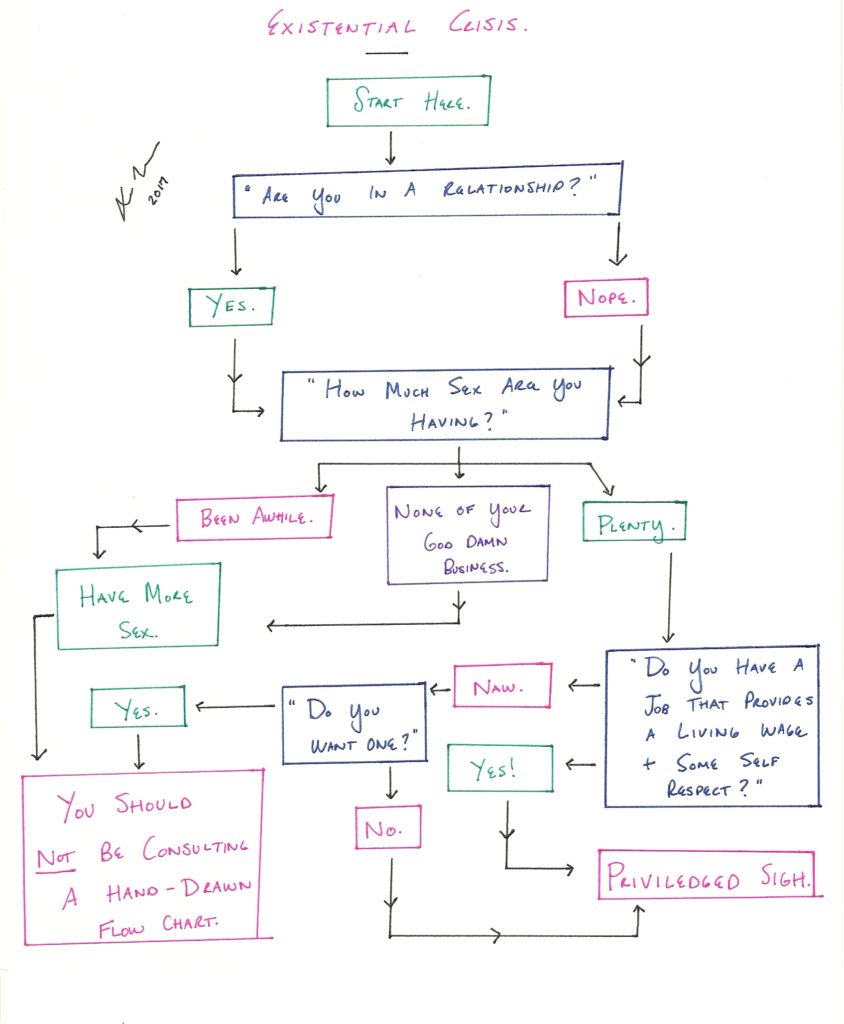

An “easy to follow” flow chart below to help you navigate your next existential crisis:

—

—

Please note that there are only two ways out of your existential crisis: “Privileged Sigh” or “Not…Consulting a Hand-Drawn Flow Chart.”

Today was a beautiful, sunny day in San Francisco – a respite from the torrents of rain that have defined this past winter in the Bay Area. I took a glorious walk in a sleeveless shirt and went through the motions of peaceful day: laundry, dish washing, reading.

Nearly 2,000 miles southeast of San Francisco, it was also a sunny day. In Houston, my father commenced his daily post-employment routine of exercising, sitting at the library, and going to temple. He made it to temple, but uncharacteristically left early to call my sister. He was sad, he told her. He was sad because 42 years ago today was the Fall of Saigon – forever changing the course of his life and, to some extent, mine.

I was not surprised to hear this. 42 years is a long time. Although time is supposedly an antidote to pain, I don’t find much truth in the idea that time heals. I think time obfuscates our memories and morphs them into happier or more anguished iterations. Worst of all, time seems to repeat itself. Another April 30 will come and go. My father will feel sad. I will feel reflective and write again about our loss. Years will pass and our collective political memory of Vietnam will fade, but will repeat itself in Afghanistan, then Iraq, and now Syria.

On April 30th’s of the past, I’ve often written long pieces about the implications of this day on the Vietnamese American community – the permanent feeling of being a tourist in our homeland; my broken ability to speak the language that connects me to Vietnam; the obstacles that my family had to overcome to acquire stability and normality on this land. Now, at the age of 30 on this April 30th, I’m most concerned about the normality of this day. My father and mother are the last connections I have to “authentic” Vietnamese culture. As I think about the family I would like to start one day, I worry that my children will think of Vietnamese history as foreign history and that they’ll never have the memory of hearing the stuttered, syncopated rhythm of the Southern Vietnamese anthem that haunted my childhood. April 30 will be a normal day of intellectual importance for them, not personal importance.

It’s a sunny, yet sad day for all of us.

—

Please see below for an excerpt from Rory Kennedy’s excellent documentary, Last Days in Vietnam. Although the entire film is well made, the 3 minutes below features a poignant story of reflagging ships flying Southern Vietnamese flags with American flags.

Since the election, I’ve read quite a few articles instructing people of privilege on how they can better engage with those who are more disenfranchised. Save for a few thoughtful pieces on how people should learn to actively listen, I am generally against catch-all pieces of writing that forcefully instruct people on how to live, how to speak, and how to interact with others. I recoil when I am told how to be, especially if it is presented in a generalized manner. I imagine others would do the same.

However, I do believe there’s an interesting post-election story on American culture that must be discussed. It’s a story of American society, particularly the upper echelons of American society, feeling like a predominantly white experience – from our food to our social rules of engagement to the way in which we are expected to speak. If you’re like me – a person who grew up on the fringes of the white American experience – the expectation has been to conform to the more dominant, often white culture. Very rarely have people conformed to my experiences, my story.

—

A story:

As some may know, I grew up in the suburban stretches of Houston, Texas. There is a long, storied road in Houston named Bellaire Boulevard that runs from the city’s wealthiest enclaves and cuts southwest – past our museums, past Rice University, and into an amalgamation of Chinese and Vietnamese strip malls. The further west the road penetrates, the poorer, yet more ethnically diverse its surrounding constituents and buildings are. Until I turned 18, I lived near the final western leg of Bellaire Boulevard that was within Houston’s city limits in a neighborhood known as Alief.

At the turn of the 19th century, Alief was essentially farmland and, to date, I still drive several Farm-to-Market (FM) roads when I head home to see my mother. The area’s pastures soon became paved roads for wealthy white suburbs. By the time my parents cobbled together enough cash and signatures to purchase our first Alief home in the late 1980s, we were participants in the area’s next big transformation: white flight. Each year, I drive down Bellaire Boulevard to the same cyclical trend – the shuttering and grand opening of noodle shops, billiards with windows that become more heavily tinted with each drive, and grocery stores whose products and patrons reflect the Latino, Vietnamese, Chinese, and African American demographic of this 20th century community.

This is where my narrative and interactions with white culture begin – a childhood spent not really interacting with white people other than my teachers. My count of close white peers in my life from age 5 to age 18 is literally 7. If you add all 5 members of the Spice Girls and all of the tolerable characters from the Babysitter’s Club, perhaps you can reasonably bring the count of people to 16.

—

If race and socio-economic status are inextricably linked, here are some of the stories I told myself growing up in a neighborhood like Alief: Parents don’t have careers, they just have jobs like janitor, machinist, or assembly line worker. Non-Vietnamese restaurants, like Olive Garden, are fancy restaurants that you only go to after middle school dances, homecoming and prom. The term “vacation” meant heading 60 miles southeast to Galveston, where the shores of the Gulf of Mexico churned crests of not blue, but brown, salty water. A longer vacation would take you towards Austin or New Orleans, while a vacation for the “lucky” meant heading as far as the country’s eastern or western shores to New York or California.

—

Here are stories I had to teach myself as I fumbled my way through predominantly white spaces:

In college, where a vast majority of my peers were white, I learned that people engage in semi-serious conversation while eating dinner. Learning how to talk at dinner was significantly harder for me than learning how to engage in a college classroom. In my adolescence, dinner was consumed quietly in 30 minutes. Occasionally, a parent would yell at one of their two children in Vietnamese. One of us would slowly respond in broken Vietnamese or English. It was a contrast to the university cafeteria overlooking the Potomac River, where conversation went quickly, reaching into personal travel I couldn’t relate to, books I had never read, in English that I thought I had mastered fluently only to find that people can simultaneously speak the same language, yet not understand each other. I learned to love those dinners, but only after I figured out how to strategically enter those conversations.

I learned that there was a world beyond gossip and politics – the conversational topics of choice in my Vietnamese family – and that I will constantly feel like I am playing cultural catch up. Films were not just Steven Spielberg or Disney – they could also be noir, avant garde, post-modern, cult classics. Music went beyond what played on the radio – it could be taste and records passed down generationally from parent to child. There was a thing called “National Public Radio” that millions of people listened to learn about issues beyond the 36 square miles you grew up in. There were places to go beyond the United States and Vietnam. Time now feels very truncated as I try to get acquainted with an American culture I supposedly knew.

I also had to learn who Bon Iver is because, for some reason, all the white people I know liked Bon Iver.

I’ve learned to dislike well-intentioned conversational questions about my childhood. These are the kind of questions that attempt to bring someone in, but feels like a “this was our collective experience, now tell me about yours” conversation – like an anthropological study of otherness.

Most of all, I learned how to manage constant homesickness because my story is never the American story – rather, it’s the narrative of constant learning, always feeling behind, and relentless catching up at the expense of cultivating the cultural roots of the America I was once from.